Professor Bottero on gods "dying of violent means" in Mesopotamian myths, and their descent into an underworld to await a resurrection to aid their human adorers , motifs of the Ancient Near Eastern world, anticpating by several hundred years similar motifs appearing in Christianity's teachings (somewhat like Christ's violent death, descent into Hell and ressurection for his adorers):

"The death of a god, of which we find only a few documented examples, was always violent and intentional. In Atrahasis the (minor) god We is deliberately immolated by his peers in order to allow a "superior" element to be introduced into human nature. And the same is true of the rebellious god Qingu in the Epic of Creation. But "death" could also be of only analogous importance. Like "deceased" humans (de-functi), that is, those who have become inactive once their "function" in life on earth had been accomplished, the gods to whom religious vicissitude had ceased to attribute an active role...were imagined to have been assigned, like us, to an infernal retirement. They were withdrawn from their interventions, which were then transferred to other members of the divine personnel, and were "dead" to the devotion of humans, even if, unlike the latter, they sluggishly conserved their supernatural perogatives, ready to come back to life if only their adorers would need them once again."

(pp. 61-62. Jean Bottero. Religion in Ancient Mesopotamia. University of Chicago Press. 2001. Bottero is Emeritus Director of l'Ecole Pratique des Hautes Etudes, quatrieme section, Paris, France)

Heidel also noted that in some Mesopotamian creation myths of mankind by the gods that man was created of the flesh and blood of a slaughtered minor god mixed with clay. Man was made to end the toil of the lesser earth dwelling gods, permitting them eternal rest from toil, which consisted of growing, harvesting and presenting food and drink to the heaven-dwelling gods.

"Enki opened his mouth and said to the great gods ...Let them slay a god...with his flesh and blood mix clay. God and Man...united (?) in the clay."

(p. 67. Alexander Heidel. The Babylonian Genesis, the Story of Creation. [2d edition], University of Chicago Press. 1942, 1951, reprint 1993)

Heidel notes another creation account, detailing that man was made to serve the gods, keep their bellies full:

"Let us slay (two) Lamga gods. With their blood let us create mankind. The service of the gods be their portion, for all times. To maintain the boundary ditch, to place the hoe and basket into their hands...to raise plants in abundance...to fill the granary...to celebrate the festivals of the gods...to pour out cold water in the great house of the gods...that they should increase ox, sheep, cattle, fish and fowl, the abundance of the land..."

(p. 70. Alexander Heidel. The Babylonian Genesis, the Story of Creation. [2d edition], University of Chicago Press. 1942, 1951, reprint 1993)

Bottero cites a Mesopotamian hymn mentioning that at night the gods and goddesses retire to their heavenly bedchambers to sleep:

""The gods and goddesses of the country-

Shamash, Sin, Adad and Ishtar-

have gone home to heaven to sleep,

they will not give decisions or verdicts (tonight).

Night has put on her veil...

Shamash the just judge, the father of the underprivileged.

has (likewise) gone to his bedchamber."

(p.185. Jean Bottero. Religion in Ancient Mesopotamia. Chicago. University of Chicago Press. 2001)

The Psalmist appears to be accusing God of sleeping, and ignoring the plight of his people, he asks God to awake, rise up, and save his people from their oppressors:

Psalm 44:11-26 RSV

"Thou hast made us like sheep for slaughter, and hast scattered us among the nations...Rouse thyself! Why sleepest thou, O Lord? Awake! Do not cast us off for ever! Why dost thou hide thy face? Why dost thou forget our affliction and oppression?...Rise up, come to our help! Deliver us for the sake of thy steadfast love! "

When Innana/Ishtar descended into the underworld to visit her sister, who was its queen, she paid for her temerity with her life. She was KILLED by her sister and her naked FLESHLY CARCASS was hung on a stake. Her "father" Enki (Ea) at Eridu in Sumer (modern Iraq) after three days and three nights sends a sexless being called Asusunamir into the underworld to restore to life Inanna/Ishtar's fleshly carcass. Asusunamir brings "bread of life and water of life" from Eridu and sprinkles them on Ishtar, she is brought back to life and in her FLESHLY body she ascends out of hell, with her clothes restored to her to live once again at the Sumerian city of Unug, also called Uruk and Kullab. The Sumerians called the uncultivated plain about their cities edin/eden, so, in a sense, when Inanna/Ishtar is restored back to fleshly-life to dwell at Uruk where she has a city-garden, she is taking up residence_in_ her city-garden surrounded by edin/eden and in Christian myth the restored dead will also dwell with God in a Garden of Eden in a city called Jerusalem. (cf. pp. 80-84. "The Descent of Ishtar to the Nether World." James B. Pritchard, editor. The Ancient Near East, An Anthology of Texts and Pictures. Princeton University Press. 1958)

The Mesopotamian myths do mention some humans, however, who do not experience death, notably, Utnapishtim and wife (along with his pilot), he is the Mesopotamian equivalent of Noah and the Ark. After the flood which destroyed all mankind (except those on the Ark) these three people are placed in a wonderous garden called Dilmun, evidently located in the marshlands of southern Mesopotamia, at the mouths of the Tigris and Euphrates river and there they live for all eternity, lying about on their backs, not having to endure the back-breaking toil the gods have ordained for the rest of mankind! That is, Utnapishtim, wife and pilot --IN THE FLESH-- never die! (cf. pp. 24-35. "The Odyssey of Gilgamesh." Fred Gladstone Bratton. Myths and Legends of the Ancient Near East. New York. Barnes & Noble. [1970], 1993)

Bottero on Utnapishtim's immortality:

"Just as one might speak of the death of a few gods, so endless life was sometimes granted to a few humans, as we see in the Epic of Gilgamesh, in which the survivors of the Flood, Utnapishtim and his wife, were made immortal by the gods and existed all alone until the end of the world."

(p.62. Jean Bottero. Religion in Ancient Mesopotamia. University of Chicago Press. 2001)

Now in Mesopotamian myths, everyone else dies, but although the flesh dies, the individual still exists in the underworld as a "dis-embodied" spirit-being, and can be be summoned up from that world on rare occasions. Gilgamesh is allowed to see and speak to his dead friend Enkidu and in the Bible King Saul is allowed to speak to the dead prophet Samuel through the efforts of the Witch of En-Dor (I Sam 28:3-19).

Wolkstein and Kramer on the Sumerian notion about death being ONLY of the fleshly body (Speaking about the death of Inanna/Ishtar and of mankind), suggesting for me, that to be restored to life, the Flesh must be brought back to life and resurrected from the grave to live once again upon the earth's surface:

"The fate Inanna has chosen is the same that awaited every mortal Sumerian. However, from archaeological evidence and literary texts, it does not seem that the Sumerians believed death was the end. For them, death marked the separation of the body from the spirit. The body was buried in the ground; the spirit moved on to a different realm in the Kur...the Sumerians believed that although no one returns from the underworld, death is not completely final. The body disintegrates, yet the transformed spirit is still recognizable."

(p. 159. Diane Wolkstein & Samuel Noah Kramer. Inanna, Queen of Heaven and Earth, Her Stories and Hymns From Sumer. New York. Harper & Row, Publishers. 1983. ISBN 0-06-090854-8 pbk)

The bottom line in all these myths is that the Gods existed _IN THE FLESH_, just as human flesh experiences hunger and needs earthly food to sustain this flesh, so too the gods need their fleshly bodies to be sustained by earthly food in the form of sacrifices. The gods fleshly bodies, like human bodies, tire and need rest and sleep; their fleshly bodies can be slain, and die. All mankind also exists in the flesh, and all flesh dies.

As noted above by Wolkenstein and Kramer the dead still "live" in the form of disembodied "spirits" in the underworld. To be "restored to life" in Mesopotamian belief is to once again possess a body of flesh and dwell upon the earth's surface.

Restoration to life, as in the example of Inanna/ Ishtar, is a "restoration to life" of THE FLESH which then lives upon the earth's surface! Here, we have the reason why man, to be "restored to life" in the Old Testament (Ezekiel's dry bones Ez 37:1-14) _and_ New Testament (Rev 20:6), has to be brought "back to life" IN A FLESHLY BODY and live once again on the earth's surface at Jerusalem.

It would take Christianity almost 300 years to triumph over the religious beliefs of the Hellenized world. Why so long? One reason was that the Greeks despised the flesh as corrupt and saw it as a tomb imprisoning an immortal soul seeking to escape and return to its heavenly father, as enunciated by Plato. The Christian notion of the dead being restored to corrupt, fleshly bodies, apparently an Ancient Near Eastern Mesopotamian notion, was "abhorrent" to Hellenistic Greek thinking.

Bibliography:

Jean Bottero. Religion in Ancient Mesopotamia. Chicago. University of Chicago Press. 2001.

Fred Gladstone Bratton. Myths and Legends of the Ancient Near East. New York. Barnes & Noble. [1970], 1993.

Benjamin R. Foster. From Distant Days, Myths, Tales and Poetry of Ancient Mesopotamia. Bethseda, Maryland. CDL Press. 1995.

Alexander Heidel. The Babylonian Genesis, the Story of Creation. [2d edition], University of Chicago Press. 1942, 1951, reprint 1993.

Othmar Keel. The Symbolism of the Biblical World, Ancient Near Eastern Iconography and the Book of Psalms. New York. The Seabury Press. A Crossroad Book. 1978 [originally published in 1972 as Die Welt der alterorientalischen Bild-symbolik und das Alte Testament: Am Beispiel der Psalmen. Benziger Verlag Zurich Einsiedeln Koln und Neukirchener Verlag Neukirchen).

James B. Pritchard, editor. The Ancient Near East, An Anthology of Texts and Pictures. Princeton University Press. 1958.

Diane Wolkstein & Samuel Noah Kramer. Inanna, Queen of Heaven and Earth, Her Stories and Hymns From Sumer. New York. Harper & Row, Publishers. 1983.

Why a Resurrection of Flesh and Blood?

(The Pre-biblical origins of a restoration from death)

Please click here for this website's most important article: Why the Bible Cannot be the Word of God.

For Christians visiting this website _my most important article_ is The Reception of God's Holy Spirit:

14 August 2003

Revisions and Updates through 01 June 2008

Christianity stresses that all the dead will be resurrected to life in reconstituted bodies of flesh and blood, be judged, and those who lead exemplary lives in Christ will obtain immortality while the sinners will go through a "second death." (Rev 20:6,14). Where are these ideas coming from? This brief article attempts to trace the "pre-biblical origins" of this concept.

Most individuals acquainted with the Old Testament recall Daniel mentioning a resurrection of the dead (Dan 12:2) and also a vision of Ezekiel's (Ez 37:1-14) where he sees a valley of bones of dead Israelites, whom God brings back to life by reconstituting their bodies, rebuilding sinew and flesh upon their "dry" bones, and then causing a wind to enter them, restoring breath to them.

We are told that Adam sinned and died and so it is for all mankind. All flesh perishes. Whence these notions?

The origins lie in ancient Mesopotamian beliefs which predate the Bible by some three thousand years. According to these myths the gods made man to be their slave to toil on earth for them, growing food to feed them, so that they themselves no longer have to toil on the earth for their food. Surprisingly these myths reveal that the gods can die and possess fleshly bodies! They can experience hunger, fatigue, a need to to rest, and a need to sleep. According to one myth a rebel god is slain, his FLESH is ground up and mixed into clay, creating mankind at Nippur. This myth stresses that the animating life force in man, his heartbeat, is to remind man that a god's spirit of "ghost" dwells within man, so a god's shed blood "animates" or gives "life" to the clay that is man. How appropriate that later Christian myths have a god's shed blood giving life to man making posible his restoration to life from death, Christ being slain to redeem man from death's power.

Professor Foster notes how the Igigi gods on earth were forced to toil ceaselessly to provide food for the Annuna (Annunaki) gods at Nippur in ancient Sumer. Their constant "clamor" over this injustice disturbs the rest and sleep of the Annuna gods, who decide to have man created of a slain rebel Igigi god and this god's "flesh and blood ground into the clay" to make man who will be a "slave to the gods," permitting all the gods, Igigi and Anunnaki, to enjoy an eternal rest and freedom from earthly toil. Man will clear the irrigation ditches, grow and harvest the food needed by the gods and present this food to them via sacrifices in the temples. That is to say, man was created to keep the gods' bellies full and relieve them of toil, so they they might enjoy an eternal rest from their labors. In other words the gods obtained their eternal Sabbath Rest from earthly toil by creating man to work in their place to provide them with life's necessities: food, clothing and shelter. The god's city-gardens have fruit trees and are surrounded by an uncultivated land called in Sumerian edin/eden. Thus man was created by the gods to toil forever in the gods' gardens in edin/eden making possible the gods' eternal Sabbath Rest from toil.

"They slaughtered Aw-liu, who had the inspiration, in their assembly.

Nintu mixed clay with his flesh and blood.

That same god and man were thoroughly

mixed in the clay.

From the flesh of the god [the] spirit remained.

It would make the living know its sign,

Lest he be allowed to be forgotten, [the] spirit remained.

After she had mixed that clay.

She summoned the Anunna, the great gods.

The Igigi, the great gods, spat upon the clay.

Mami made ready to speak,

And said to the great gods,

"You ordered me the task and I have completed it !

"You have slaughtered the god, along with his inspiration.

I have done away with your heavy forced labor,

I have imposed your drudgery on man.

You have bestowed (?) clamor on mankind."

(p.59. "Gods and their deeds." Benjamin R. Foster. From Distant Days, Myths, Tales and Poetry of Ancient Mesopotamia. Bethseda, Maryland. CDL Press. 1995. Foster is a Professor of Assyriology at Yale University)

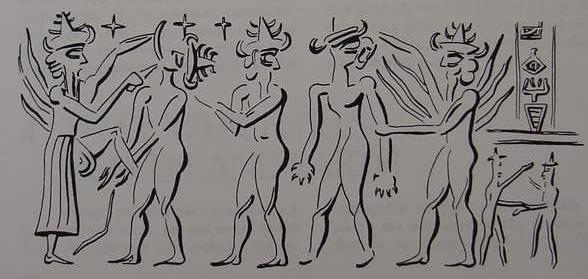

Below, a cylinder sealing showing, what _I understand_ to be captive gods being led to a slaughter. The fiery god with flames erupting from his back on the viewer's far left, appears to be slashing the throat of a captive god with a knife, whose arms are extended before him in a submissive manner, the next god, looking over his shoulder appears to have his hands bound before him, the next possesses a monster head and is held by the arm by a god possessing a fiery body, with flames erupting from his back (cf. figure 53. p. 54. Othmar Keel.

The Symbolism of the Biblical World, Ancient Near Eastern Iconography and the Book of Psalms. New York. The Seabury Press. A Crossroad Book. 1978 [originally published in 1972 as Die Welt der alterorientalischen Bild-symbolik und das Alte Testament: Am Beispiel der Psalmen. Benziger Verlag Zurich Einsiedeln Koln und Neukirchener Verlag Neukirchen).